The human eye sees by light stimulating the retina (a neuro-membrane lining the inside back of the eye). The retina is made up of what are called Rods and Cones. The rods, located in the peripheral retina, give us our night vision, but can not distinguish color. Cones, located in the center of the retina (called the macula), are not much good at night but do let us perceive color during daylight conditions.

The human eye sees by light stimulating the retina (a neuro-membrane lining the inside back of the eye). The retina is made up of what are called Rods and Cones. The rods, located in the peripheral retina, give us our night vision, but can not distinguish color. Cones, located in the center of the retina (called the macula), are not much good at night but do let us perceive color during daylight conditions.

The cones, each contain a light sensitive pigment which is sensitive over a range of wavelengths (each visible color is a different wavelength from approximately 400 to 700 nm). Genes contain the coding instructions for these pigments, and if the coding instructions are wrong, then the wrong pigments will be produced, and the cones will be sensitive to different wavelengths of light (resulting in a color deficiency). The colors that we see are completely dependent on the sensitivity ranges of those pigments.

Many people think anyone labeled as “colorblind” only sees black and white – like watching a black and white movie or television. This is a big misconception and not true. It is extremely rare to be totally color blind (monochromasy – complete absence of any color sensation). There are many different types and degrees of colorblindness – more correctly called color vision deficiencies.

People with normal cones and light sensitive pigment (trichromasy) are able to see all the different colors and subtle mixtures of them by using cones sensitive to one of three wavelength of light – red, green, and blue. A mild color deficiency is present when one or more of the three cones light sensitive pigments are not quite right and their peak sensitivity is shifted (anomalous trichromasy – includes protanomaly and deuteranomaly). A more severe color deficiency is present when one or more of the cones light sensitive pigments is really wrong (dichromasy – includes protanopia and deuteranopia).

5% to 8% (depending on the study you quote) of the men and 0.5% of the women of the world are born colorblind. That’s as high as one out of twelve men and one out of two hundred women. I am going to limit this discussion to protans (red weak) and deutans (green weak) because they make up 99% of this group.

Protanomaly (one out of 100 males) :

Protanomaly (one out of 100 males) :

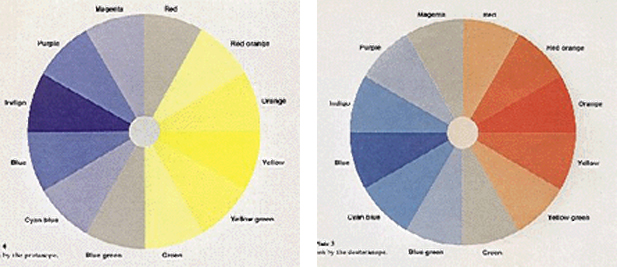

Protanomaly is referred to as “red-weakness”, an apt description of this form of color deficiency. Any redness seen in a color by a normal observer is seen more weakly by the protanomalous viewer, both in terms of its “coloring power” (saturation, or depth of color) and its brightness. Red, orange, yellow, and yellow-green appear somewhat shifted in hue (“hue” is just another word for “color”) towards green, and all appear paler than they do to the normal observer. The redness component that a normal observer sees in a violet or lavender color is so weakened for the protanomalous observer that he may fail to detect it, and therefore sees only the blue component. Hence, to him the color that normals call “violet” may look only like another shade of blue.

Under poor viewing conditions, such as when driving in dazzling sunlight or in rainy or foggy weather, it is easily possible for protanomalous individuals to mistake a blinking red traffic light from a blinking yellow or amber one, or to fail to distinguish a green traffic light from the various “white” lights in store fronts, signs, and street lights that line our streets.

Deuteranomaly (five out of 100 males):

The deuteranomalous person is considered “green weak”. Similar to the protanomalous person, he is poor at discriminating small differences in hues in the red, orange, yellow, green region of the spectrum. He makes errors in the naming of hues in this region because they appear somewhat shifted towards red for him. One very important difference between deuteranomalous individuals and protanomalous individuals is deuteranomalous individuals do “not” have the loss of “brightness” problem.

From a practical stand point, many protanomalous and deuteranomalous people breeze through life with very little difficulty doing tasks that require normal color vision. Some may not even be aware that their color perception is in any way different from normal nor do their friends. The only problem they have is passing that “Blank Blank” color vision test.

Dichromasy – can be divided into protanopia and deuteranopia (two out of 100 males):

These individuals normally know they have a color vision problem and it can effect their lives on a daily basis. They see no perceptible difference between red, orange, yellow, and green. All these colors that seem so different to the normal viewer appear to be the same color for this two percent of the population.

Protanopia (one out of 100 males):

Protanopia (one out of 100 males):

For the protanope, the brightness of red, orange, and yellow is much reduced compared to normal. This dimming can be so pronounced that reds may be confused with black or dark gray, and red traffic lights may appear to be extinguished. They may learn to distinguish reds from yellows and from greens primarily on the basis of their apparent brightness or lightness, not on any perceptible hue difference. Violet, lavender, and purple are indistinguishable from various shades of blue because their reddish components are so dimmed as to be invisible. E.g. Pink flowers, reflecting both red light and blue light, may appear just blue to the protanope.

Deuteranopia (one out of 100 males):

The deuteranope suffers the same hue discrimination problems as the protanope, but without the abnormal dimming. The names red, orange, yellow, and green really mean very little to him aside from being different names that every one else around him seems to be able to agree on.

In Conclusion:

It should be obvious there are several different kinds and degrees of color vision deficiencies. Protanomalous or deuteranomalous individuals can usually pass as a normal observer in everyday activities. They may make occasional errors in color names, or may encounter difficulties in discriminating small differences in colors, but usually they do not perform very differently from the normal except on color vision tests.

The protanope and deuteranope, on the other hand, can be severely color deficient. The real problem, as a protanope or deuteranope may see it, is there are far too many hue names (color names) used by most people without any obvious basis for using one instead of another. Why call something “orange” when it doesn’t look different in any way from something else called green, tan, beige, or any of several other color names?